January 18, 2019

Reflections on the Proposed UK Skills-Based Immigration System and the Social Care Sector

Reflections on the Proposed UK Skills-Based Immigration System and the Social Care Sector

By Professor Shereen Hussein and Dr Agnes Turnpenny Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent, Canterbury

The Government’s White Paper on the UK’s future skills-based immigration system (White Paper) published on 19/12/2018 represents a radical departure from the existing system of labour migration.

The Government’s attempt to address post-Brexit immigration in a systematic way is welcome and the acknowledgment of social care as a sector especially affected is significant. The proposed plans have serious consequences for the fast-growing sector of social care including employers, workers, service users, and family carers. Drawing on workforce data from the National Minimum Dataset for Social Care (NMDS-SC) and existing research, this commentary aims to highlight some of the key implications on the sector within a context of policy changes since 2004. The latter have made it difficult for employers to have sustained recruitment strategies (for both skilled and less-skilled jobs in the sector) and increased the reliance on EU migrants to fill gaps.

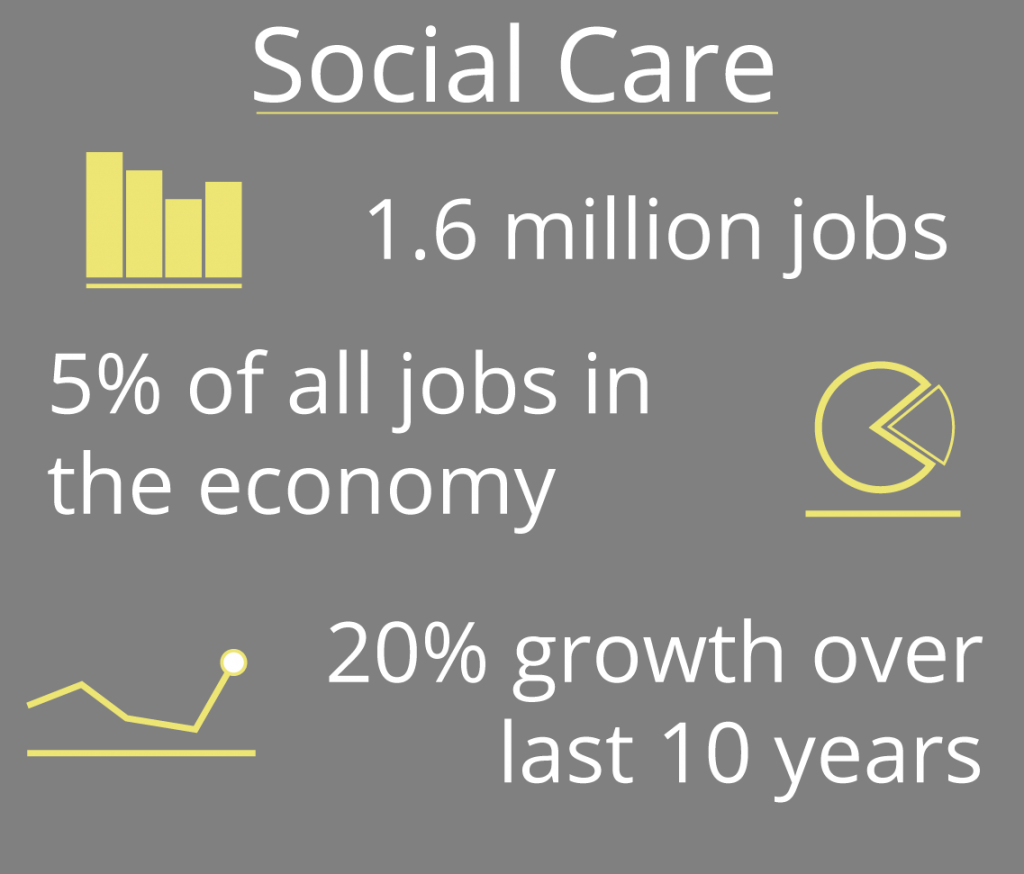

With 1.6 million jobs, social care represents over five per cent of all jobs in the economy and has seen a rapid growth – by more than 20% – over the last 10 years (Skills for Care 2018). Nearly 80% of the jobs are in the independent sector. The role of private/for-profit providers in social care has expanded due to a complex set of drivers: marketisation, personalisation, and austerity. This has resulted in a complex and fragmented landscape of services with over 20 thousand organisations involved in the provision of social care ranging from micro-providers to large chains (Skills for Care 2018). Private providers are often more able to absorb cost reductions through reduced workers’ wages, rights and protection, with negative implications on the sector’s ability to attract wider pools of care workers.

Vacancy and turnover rates have been persistently high in the sector due to various reasons (Hussein et al. 2016).[1] In 2018, the vacancy rate for direct care workers has stood at 8.6% and annual turnover at 34.8% in 2018 (NMDS dashboard), significantly higher than the national average. Hussein (2017) estimated that at least 10 to 13% of direct care workers were paid below the (statutory) national minimum wage.[2] Furthermore, one in four workers in the sector (and over 50% in home care) are employed on ‘zero-hour contracts’ (NMDS-SC Workforce Estimates 2017-18).

The above highlights the context for the sector’s reliance on migrant workers, who currently make up 18% of the workforce: 8% are EEA (non-British nationals) and 10% are non-EEA nationals. The share of migrants in the workforce varies substantially between regions: it is much higher in London and the South East (39% and 23% respectively) compared to only four per cent in the North East of England. Non-British workers are less likely to hold managerial positions, however they are over-represented in regulated professions (nursing, social work) and direct care work (NMDS-SC Workforce Estimates 2017-18).

While migrant workers have traditionally contributed to social care, their composition has shifted since 2004. Free movement of EU nationals from ‘accession countries’ in Central and Eastern Europe, and restrictions on the direct recruitment (and in some cases retention) of non-EEA workers following the introduction of the points-based visa system in 2008, has resulted in an increased reliance on EEA workers, particularly from Romania and Poland, and a decline in the overall share of non-EEA workers. Romanian and Polish nationals now represent the two largest nationality groups in social care followed by the Philippines, Nigeria, India, and Zimbabwe.

Existing research highlights that demand for the recruitment of migrant workers is driven by local labour shortages, generally attributed to poor working conditions in the sector; one of the perceived ‘advantages’ of migrant workers as reported by employers is their willingness to accept less favourable working conditions (Cangiano & Shutes, 2010, Hussein, Stevens & Manthorpe 2011).[3] This calls into question the sustainability of the sector’s recruitment strategies and how these interact with the UK immigration system.

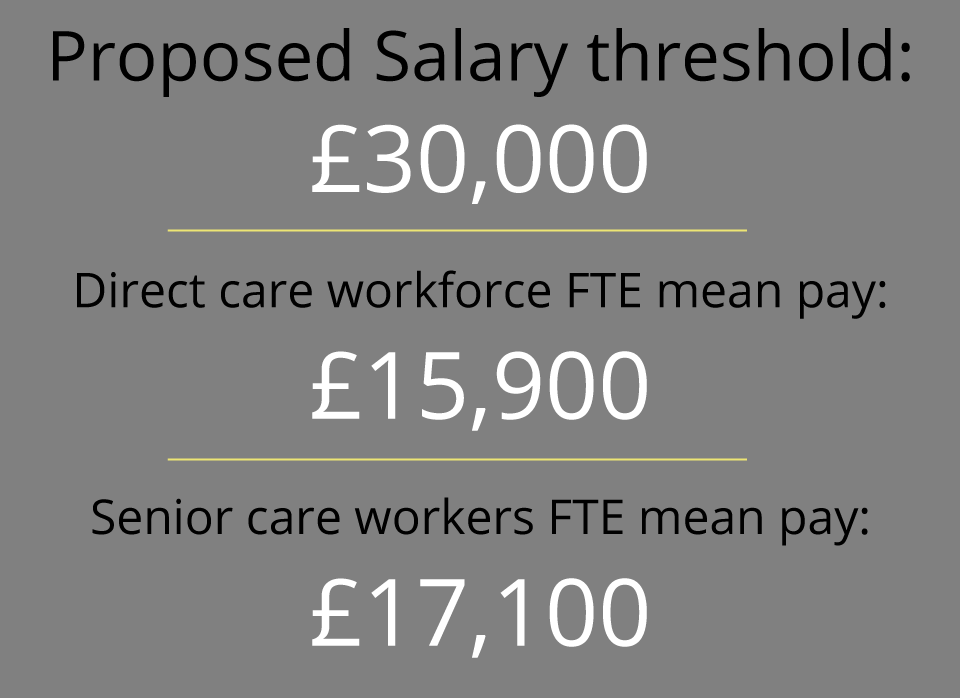

Under the Government’s proposal free movement of EU (EEA) nationals will end from January 1, 2021 and a single route will be introduced for ‘skilled workers’ from all countries.[4] It is envisaged that this will be open to all occupations with a skill level of RQF3 and above subject to a salary threshold, currently £30,000 per year[5] but under consideration. The cap on the number of visas issued will be lifted and the sponsorship system will be replaced by a ‘lighter-touch’ streamlined approach compared to the current Tier2 requirements (however, safe to say it is likely to be substantially heavier and onerous than free movement where the process of hiring EEA nationals is largely the same as hiring UK nationals).

One of the central tenets of the new immigration policy is the end of ‘low-skill labour migration’, therefore no specific route is proposed for ‘lower skilled workers’. Instead, a time-limited route for temporary short-term workers is planned that will allow people to come for a maximum of 12 months with limited rights: no access to public funds, no dependants in the UK, and no return within 12 months to prevent people effectively settling in the country. This route would not be subject to sponsorship and short-term workers could change employers during their stay. Short-term migrant workers would have to pay a visa fee, “which may, in this instance, rise over time, reflecting the transitory nature of this scheme” (p. 17). No sectoral schemes are proposed, with the exception of agriculture.

Social care is mentioned throughout the White Paper as one of the sectors that would face challenges and “find it difficult immediately to adapt” but the Government states it is “committed to working (…) to help facilitate the change needed to reduce demand for low skilled migrant labour” (pp. 16-17).

From the social care perspective, such challenges in maintaining adequate workforce may arise from the following:

- Salary threshold: although senior care workers would be permitted under the new skilled route, the proposed threshold of £30,000 means that very few would actually qualify.[6] Pay estimates from Skills for Care (2018) show that the full-time equivalent (FTE) mean annual pay of the direct care workforce (including senior care workers) is £15,900 in independent provision (where 95% of these jobs are and where the majority of migrants work). Even for senior care workers the FTE mean pay is £17,100, well below the suggested salary threshold.

- Removal of the cap on the number of work visas: this would make the recruitment of social workers and registered nurses (regulated professions) from non-EEA countries easier as current pay is closer to the threshold in this category (£34,900 in local authority and £29,200 in independent sector provision).

- Sponsorship: although a lighter-touch streamlined system is proposed this would still be a – financial and administrative – burden for employers, particularly for small and micro-providers that so far could rely on EU migrants to fill vacancies without additional cost.

- Temporary visas for ‘low-skilled’ workers: most migrant direct care workers would only qualify under the short-term route. Increasing reliance on an ever-changing pool of short-term migrant workers might have several negative impacts

On the well-being of service users and family carers (due to many factors including lack of continuity, disruption of personal relationships, poor quality of care as employers might become more reluctant to invest in workforce training).

Care work – especially home care – can be isolating, and shorter stay would make it harder for migrant workers to settle, form relationships and networks or integrate in British society with negative impacts on workers’ wellbeing and quality of care.

The short-term visa fee would encourage reliance on recruitment agencies and increase the risk of labour exploitation. Social care is particularly vulnerable due to sectoral characteristics such as fragmentation, casualization and low pay.

- The ad-hoc nature of the short-term immigration route might fail to meet shortages in labour supply. This route would rely on migrants actively seeking to come to the UK and take-up short term employment. The effect of this on labour supply is difficult to predict – as also acknowledged by the White Paper. Particularly, social care with its low pay and emotional demands might not be an attractive option for many temporary migrants.

All in all, it is unlikely that the proposed new system would in any way address the need of the care sector to recruit migrant workers. To the contrary, it appears it might exacerbate existing labour shortages in social care with potentially far reaching implications for well-being and sustainability. As the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) report (2018) points out social care “needs a policy wider than just migration policy to fix its many problems.” Years of austerity, marketization, and growing demand from an ageing population have all contributed to the difficulties of the sector, including workforce challenges. The social care market has been suffering from severe workforce shortages over the past years with ever increasing turnover and vacancy rates. It has become increasingly reliant on EEA migrants who are free to come and seek work in the UK. However, even with free movement, the sector was not able to meet demand, which highlights the need for a specific recruitment (and retention) strategy (both from within and outside the UK) to meet the escalating demand for social care.[7] Such strategy needs to be specific and context-tailored to the emotional work and level of commitment required to provide high quality and person-centred care to the most vulnerable people in our society. It could also acknowledge the sector’s need for migrants and design a specific route to ensure adequate supply of care workers with required skills as part of a sustainable system (acknowledging the implications beyond the UK borders). There are examples across the world that the UK could learn from.

All in all, it is unlikely that the proposed new system would in any way address the need of the care sector to recruit migrant workers. To the contrary, it appears it might exacerbate existing labour shortages in social care with potentially far reaching implications for well-being and sustainability. As the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) report (2018) points out social care “needs a policy wider than just migration policy to fix its many problems.” Years of austerity, marketization, and growing demand from an ageing population have all contributed to the difficulties of the sector, including workforce challenges. The social care market has been suffering from severe workforce shortages over the past years with ever increasing turnover and vacancy rates. It has become increasingly reliant on EEA migrants who are free to come and seek work in the UK. However, even with free movement, the sector was not able to meet demand, which highlights the need for a specific recruitment (and retention) strategy (both from within and outside the UK) to meet the escalating demand for social care.[7] Such strategy needs to be specific and context-tailored to the emotional work and level of commitment required to provide high quality and person-centred care to the most vulnerable people in our society. It could also acknowledge the sector’s need for migrants and design a specific route to ensure adequate supply of care workers with required skills as part of a sustainable system (acknowledging the implications beyond the UK borders). There are examples across the world that the UK could learn from.

The Government will need to face and respond to these more urgently. The delays in the publication of the Green Paper on social care are further hindering the ability of the sector to prepare for these significant challenges.

Professor Shereen Hussein is currently leading a work stream researching at the implications of Brexit on migrant workers’ contribution to the social care sector as part of a wider ESRC-funded Programme of Work: Sustainable Care, led by Professor Sue Yeandle at the University of Sheffield. Dr Agnes Turnpenny is a research associate on the same work stream.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

All hyperlinks correct on 21/12/2018.

[1] Hussein, S., Ismail, M., & Manthorpe, J. (2016). Changes in turnover and vacancy rates of care workers in England from 2008 to 2010: panel analysis of national workforce data. Health & social care in the community, 24(5), 547-556. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12214 (open access)

[2] Hussein, S. (2017). “We don’t do it for the money”… The scale and reasons of poverty‐pay among frontline long‐term care workers in England. Health & social care in the community, 25(6), 1817-1826. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12455

[3] Cangiano, A., Shutes, I., Spencer, S., & Leeson, G. (2009). Migrant care workers in ageing societies: research findings in the United Kingdom. Oxford: COMPAS, University of Oxford http://doc.ukdataservice.ac.uk/doc/6920/mrdoc/pdf/6920report.pdf

Hussein, S., Stevens, M., & Manthorpe, J. (2011). What drives the recruitment of migrant workers to work in social care in England?. Social Policy and Society, 10(3), 285-298. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746411000029

[4] If there is a ‘no-deal’ Brexit, there will be no Implementation Period and any new rules might enter into force sooner.

[5] Lower for new graduates/entrants.

[6] There is also a lower threshold of £21,000 discussed in the media, which the Prime Minister has ruled out so far.

[7] As a side note, with increasingly severe labour shortages and ageing populations in the EU15 and EU2, the supply of EEA migrants in the UK should not be taken for granted even if free movement continued. For example Poland is now a main destination for migrant workers from outside the EU (Eurostat Newsrelease 166/2018).