March 11, 2019

By Irit Garty, Masters Student at the Tizard Centre

The use of restraint has been a popular topic in the care sector in recent years, with restrictive practice increasingly seen as unacceptable unless in extreme cases to prevent harm. The Government’s policy Positive and Proactive Care came into place in 2014, after the Winterbourne View abuse scandal. But even to date many organisations fall behind the standards outlined in this document.

Winterbourne View

What happened at Winterbourne View highlighted the dangers of restrictive practice. Those with learning disabilities perceived to be challenging experienced punishment, humiliation and pain. In order to abolish a culture that inadvertently encouraged physical and psychological abuse, an ethical policy about restrictive practice was necessary.

Until Positive and Proactive Care, no legislation about restrictive practice existed. The only non-statutory paper was “Guidance for restrictive physical interventions: How to provide safe services for people with learning disabilities and autistic spectrum disorder” (2002).

The UK Department of Health (DoH) and the Care Quality Commission (CQC) informed the development of Positive and Proactive Care. The DoH report “Transforming care” (2012) outlined actions needed to avoid cases like Winterbourne View, while the CQC inspected over 100 disability services where restrictive practice was common. They found restrictive practices were often the primary strategies for challenging behaviour.

Restraint and coercion

The use of restraint and coercion has a large literature in mental health, however there has been much less focus on people with learning disabilities and autism. Research has shown that restraint as a solution for challenging behaviour places people and their support staff at risk (Bonner et al. 2002) and has the potential to cause long-term harm. It carries a risk of psychological harm and physical injury to the individual, and even death in some cases. It can also be traumatising for staff, many of whom experience negative psychological effects when involved in restraining people (Sequeira & Halstead 2004).

Positive and Proactive Care offers a framework for delivering care that reduces challenging behaviour through the enhancement of quality of life and better meeting people’s needs. By proposing therapeutic approaches, rather than punishing attitudes, it aims to promote these principles across a range of health and social care settings so that attitudes and standards are consistent. Although restrictive interventions may occasionally be necessary for high-risk situations; this approach outlines a need for specific criteria that ensures such practice is ethical, recorded transparently, and promotes recovery.

Restrictive practice

The guiding principles of Positive and Proactive Care place emphasis on the individual’s safety dignity and respect, as well as the safety of support staff. It is suggested that restrictive practice is used within the context of positive behaviour support plans; offering a range of proactive strategies to avoid a crisis. In high-risk situations, restrictive practice may be considered as a last resort, for the shortest possible time and when all other alternatives have been attempted. There is a clear description of what is considered restrictive practice (physical restraint, mechanical restraint, chemical restraint, seclusion and long-term segregation) and a list of legal implementation measures. A crucial element of this policy is the guidance around effective organisational governance procedures including:

Positive behaviour support

To comply with this policy, organisations must nominate a board to approve, audit, review, advise and regulate restrictive practice. It must devise restriction reduction programmes and embrace evidence-based therapeutic approaches such as the Positive Behaviour Support Framework. Organisations must have Positive Behaviour Support, or a restrictive practice policy, and report on the use of restrictive interventions to service commissioners. It is the role of the CQC to audit and review organisational progress against restrictive intervention reduction programmes.

Unfortunately, Positive and Proactive Care has not delivered the expected outcomes. Statistics by NHS Digital obtained by BBC Radio 4’s File on 4, and also featured in The Guardian and The Independent newspapers, revealed that the use of restraint on adults with learning disabilities has risen by 50% in NHS mental health hospitals in England; restraint was used 22,620 times in 2017, compared with 15,065 times in 2016. The online publication Nursing Standard (2018) noted, in relation to these statistics that: “Mencap head of policy and public affairs Dan Scorer, and Challenging Behaviour Foundation chief executive Viv Cooper, warned that 2014 guidance from NHS England to reduce the use of such restrictive practices is ‘clearly not being implemented’.” In December 2018, the CQC published their plan to carry out a thematic review of the use of restrictive interventions, which has been commissioned by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. They intend to publish the outcomes in May 2019 followed by a full report in March 2020.

Strategic, cultural change

Implementation of policy always involves a strategic, as well as cultural, change. The complexity lies in the fact that these elements rely on one another and can either enhance or disable each other. Without a cultural shift, strategy is unlikely to be successful and in the absence of strategy, culture is unlikely to change.

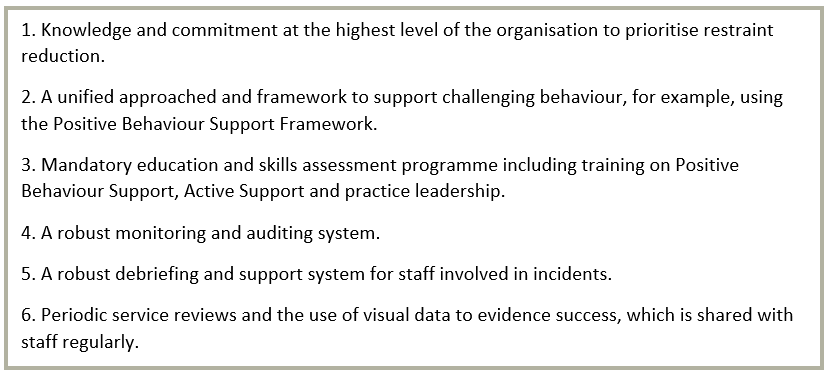

It appears that some organisations tend to implement elements of this policy; but I suggest that effective implementation requires an organisational commitment for systemic change. It is not enough to train staff or write organisational policies. The following elements are all equally crucial for leading a meaningful process:

Implementation is not always a straightforward task. The care sector suffers from rapid staff turnover. Teams are heterogeneous in terms of cultural backgrounds and values and this can impact their views on challenging behaviour. In addition, maintaining robust auditing and an ethical practice system requires time and resource. In times of austerity, services are often caught in a cycle of firefighting and do not always prioritise practices that can prevent the fire.

It seems that there is a long way to go on our journey to promote safety from physical and institutional abuse of people with disabilities.

While it is the role of organisations such as the CQC to audit services, practitioners and support staff play a vital role in making every day gradual changes for the individuals they support. Modelling compassionate and ethical care to all staff in order to extinguish inadvertent abuse of people with disabilities would provide the solid foundation required to make Positive and Proactive Care achievable.