April 29, 2020

A comment on the government’s Action Plan for Adult Social Care

By John Forth, Cass Business School, City, University of London – 28th April 2020

Download this blog post as a pdf

Over the past few weeks, it has become increasingly apparent that the social care sector sits firmly on the COVID-19 frontline. With much of the initial public and political attention focusing on the NHS, growing criticism that the sector was being forgotten or overlooked led the government last week to publish its Action Plan for Adult Social Care.[i]

The Action Plan includes a range of measures, with a number of these focusing specifically on the social care workforce. In particular, the Plan sets a target of attracting 20,000 additional workers into the adult social care sector in England within the next three months.[ii]

The target of 20,000 new entrants is laudable, with many having pointed to the workforce shortages that exist in the sector. It also looks suitably ambitious. One of the major sources of workforce statistics for the sector is the Adult Social Care Workforce Data Set (ASC-WDS) maintained by Skills for Care using workforce data from care providers. It tells us that there are typically around 45,000 new entrants to the sector per quarter in normal times.[iii] The challenges of attracting 20,000 new workers to the sector in the midst of the pandemic are then surely significant, and he newly-launched recruitment campaign will be central to the plan to attract more staff into the sector.

Where might any additional recruits come from?

To answer this question, we first look at what the typical new entrant to adult social care is doing before entering the sector. ASC-WDS contains limited information on their prior status, so Figure 1 is based on our own analysis of the Labour Force Survey – the source of many of the UK’s official labour market statistics.

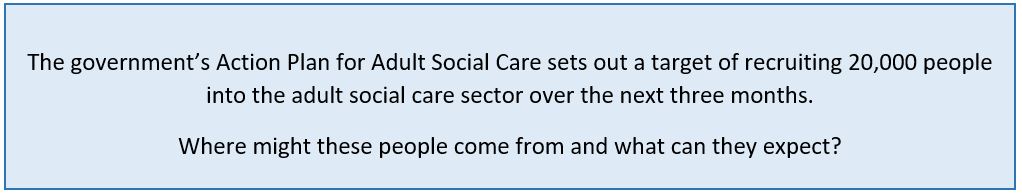

Figure 1: Prior labour market status of new entrants to Adult Social Care[iv]

Source: Longitudinal Labour Force Survey (LLFS), 2015-2018

Figure 1 shows that around one fifth (21%) of new entrants enter from unemployment, another fifth (21%) from some form of inactivity and the remaining three-fifths (58%) from other jobs. Figure 2 shows that a sizeable minority of this last group enter from the Health sector or other parts of social care (17%). It doesn’t seem likely that the recruitment campaign will be able to increase this share to any substantial degree: most healthcare workers are surely too preoccupied to be job seeking.

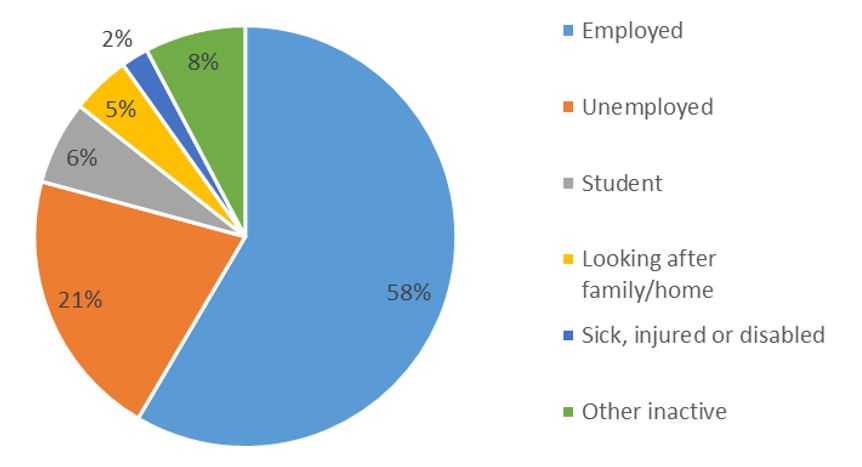

Figure 2: Previously-employed new entrants, by sector of origin

Source: Longitudinal Labour Force Survey, 2015-2018

However, the campaign may have more success in boosting the intake from the wholesale and retail sector and accommodation and food services. The large numbers furloughed from hotels, restaurants and high-street stores have little incentive to take a job in social care, but there may be more potential among those who have actually been made redundant. The question will be whether sufficient numbers of laid-off shop workers and restaurant staff – although similar in many respects to those working in social care (often female, low qualified and low paid) – can demonstrate enough transferable skills to equip them for frontline care work.

Many of those people who have recently volunteered to the NHS are, in reality, engaged in social care activities and this group has a clear opportunity to demonstrate their potential, if indeed they want to migrate to a paid position. The government has also offered free access to online training for any new recruits, covering key areas of the Care Certificate. But additional training may be needed beyond that at the local level, together with the usual on-boarding activities. Providers will therefore have to make difficult decisions about the costs and benefits of hiring inexperienced workers when resources are already stretched.[v]

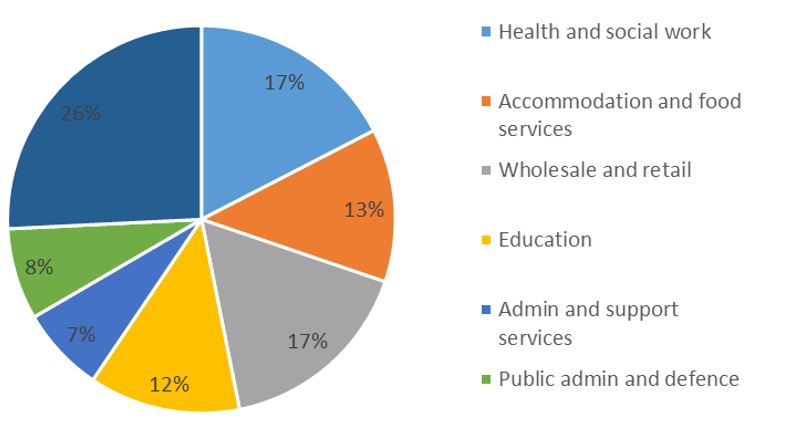

Another group highlighted in the Action Plan is returners to the sector: these, of course, are likely to have the benefit of significant prior experience. The call on returners has proved to be successful in the NHS, with many ex-GPs, nurses and other medical professionals re-joining the sector, albeit typically in supporting roles. Figure 3 shows what those workers who leave Adult Social Care are doing in the quarter after they exit. Only one-third (32%) are inactive, with around one-in-twenty newly retired, and so the number of returners is likely to be relatively small. It is possible that the physical nature of some frontline care work may also be unappealing to those of retirement age, with returnees then perhaps funnelled towards support roles rather than direct care provision – as has been the case in the NHS.

Figure 3: Subsequent labour market status of those leaving Adult Social Care[vi]

Source: Longitudinal Labour Force Survey, 2015-2018

This raises the broader question of how attractive social care will be to those looking for work in the midst of the pandemic?

What can new recruits expect?

Clearly, for some, the new recruitment campaign will bring a welcome opportunity to re-enter work and boost a household income that may have been severely dented of late. But the NHS also continues to recruit and, for those with some relevant experience, this may represent a more attractive option.

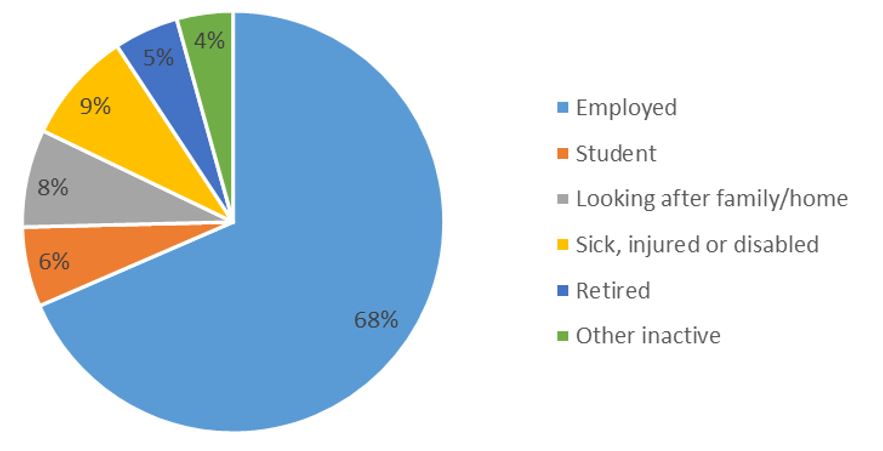

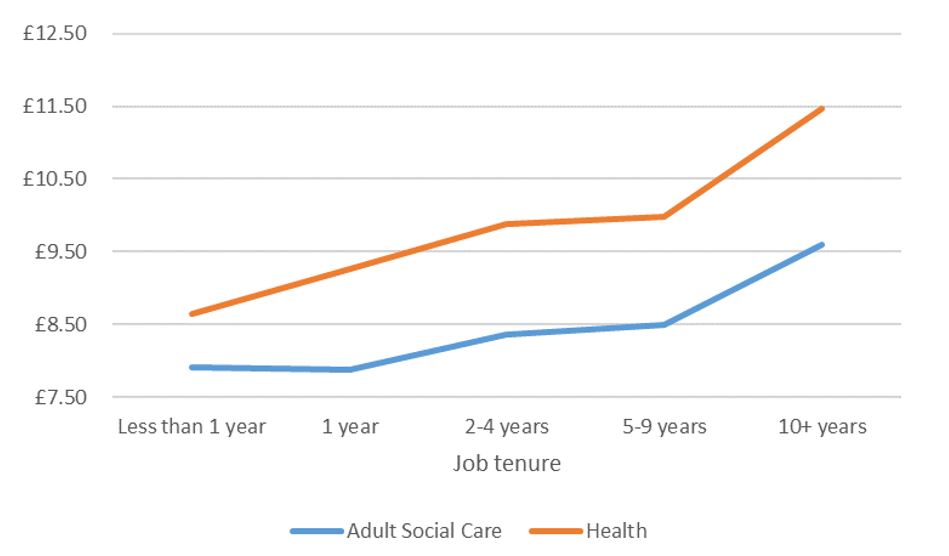

Healthcare assistants in the NHS represent a reasonably close comparator for care workers in Adult Social Care sector in terms of task content and skill requirements. Yet average earnings for a healthcare assistant stand at £10.00 per hour, compared with £8.40 for a care worker. Health care assistants are also less likely to work long hours and typically have fewer supervisory responsibilities.[vii] Long-term prospects are also better in the Health sector for those with relatively low qualifications (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Average gross hourly earnings for workers without A-levels, by job tenure and sector

Source: Quarterly Labour Force Survey, 2018

Earnings progression may not be an issue for those seeking a short-term position. However, it seems clear that the government sees the forthcoming recruitment campaign, in part, as an opportunity to attract people into the sector for more than a few months, with the Social Care Action Plan referring to its ‘long-term ambition’ to grow the social care workforce. The question then is how to keep the 20,000 new entrants in the sector when the crisis is over?

Improving retention may be as important as recruitment

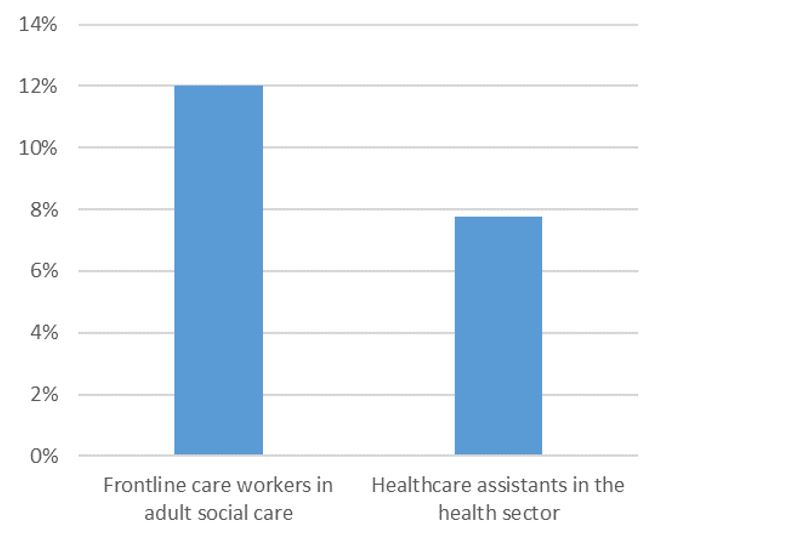

There are long-running concerns about low rates of workforce retention in adult social care. Our analysis of the Labour Force Survey over a number of years indicates that around one-in-eight frontline care workers (12%) leave the health and social care sector in a given year. Among healthcare assistants, by comparison, the share is around one-in-twelve (8%).

Figure 5: Percentage of workers leaving the health and social care sector per annum

Source: Longitudinal Labour Force Survey, 2012-2018

With around 1m people working in frontline care roles in adult social care, the number leaving the broad area of health and social care each quarter is therefore likely to be at least as high as the number of new recruits now being targeted. Stemming the outflow of workers from social care may therefore prove to be an important as recruitment in addressing workforce shortages in the long run. But of course, this requires hard evidence on what drives labour supply, recruitment and retention in social care so that care providers, commissioners and policymakers are able engage in a meaningful dialogue towards an effective and sustainable workforce. The broader package of research that we are currently undertaking for the Health Foundation will go some way to providing that evidence.

Acknowledgements and disclaimer:

This blog was produced as part of a wider project on the Retention and Sustainability of the Social Care Workforce (RESSCW), funded by the Health Foundation under its Efficiency Research Programme. The Health Foundation is an independent charity committed to bringing about better health and health care for people in the UK. Skills for Care is a strategic partner to the project.

The Labour Force Survey data were collected by the Office for National Statistics and supplied by the UK Data Archive.

None of these organisations bears any responsibility for the content or views expressed here.

Download this blog post as a pdf

Notes:

[i] Department of Health and Social Care (2020) COVID-19: Our Action Plan for Adult Social Care, Version 1.0, published 15 April 2020

[ii] See paragraph 2.12.

[iii] Skills for Care’s latest report on The State of the Adult Social Care Sector and Workforce in England, published in October 2019, estimates that there were 560,000 new starters over the 12 months to September 2018 (p.50). Some 34% of these were estimated to be new to the adult social care sector, with the remainder moving from different employers within the sector or moving within the same employer.

[iv] The LLFS follows individuals over five successive quarters. We use successive LLFS cohorts from 2015-2018. We define new entrants as those who are working in Adult Social Care in one of these quarters, not having worked there in the previous quarter. Adult social care is defined as Classes 87.10, 87.20 87.30 and 88.10 of the Standard Industrial Classification (2007).

[v] Recent qualitative work by project colleagues Agnes Turnpenny and Shereen Hussein has pointed to the demands placed on existing care workers when asked to provide on-the-job training to inexperienced recruits thrust quickly into frontline work.

[vi] Leavers are those who were employed in Adult Social Care in one quarter but not the next.

[vii] Our analysis of the 2018 Quarterly Labour Force Survey indicates that 7 per cent of healthcare assistants in the Health sector usually work 48 hours or more per week and 9 per cent have managerial/supervisory responsibilities; the equivalent figures among care workers in Adult Social Care are 14 per cent and 17 per cent respectively.